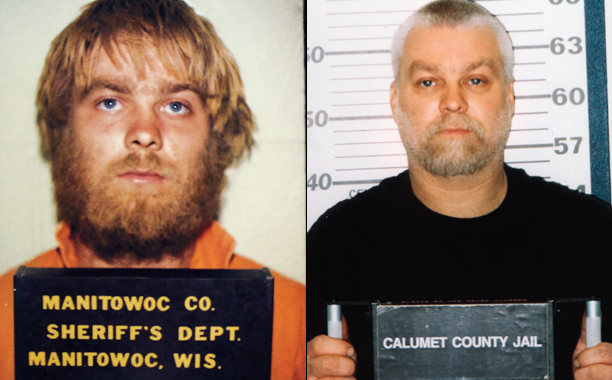

Netflix’s documentary mini-series Making A Murderer has sparked a large debate, online and in the real world, over whether or not Steven Avery is guilty of the murder of Teresa Halbach. There’s a strong argument for either case: Avery has a rough history and a wealth of physical evidence against him, but there’s also very strong reason to believe that said evidence was tampered with by a police department with a strong motive to frame him. The documentary also chooses to ignore some character-debilitating evidence that has since come to light, but such evidence is not as damning as many would like to believe. No matter how much people argue around the water cooler, it’s likely that we’ll never know for sure whether Avery is guilty of Teresa Halbach’s murder.

But what many seem to miss is that, in a way, Avery’s guilt is beside the point. Making A Murderer is far more significant for its damning indictment of the United States justice system. Not only are the basic tenants of law frequently upended or ignored, but the inherent bias AGAINST the defendant, who is supposed to be “innocent until proven guilty,” is shocking and abhorrent.

Making A Murderer does an incredible job over its 10 episodes of chronicling the absurd number of unfair advantages the prosecution is given over the defense, as well as the unethical methods police use to obtain confessions and the general lack of oversight police have in their duties. While it should be an uphill battle for the prosecution to put together a case against the defendant, we instead see how Avery is presumed guilty from the start, even when the testimonies and evidence used against him make no sense together. The way that the prosecution seems to acknowledge Brendan Dassey’s coerced confession when it’s convenient and ignore it or claim it untrue when it’s not is especially damning. In these cases, the prosecution is clearly hired to gain a conviction for the state, not to get to the truth or convict the right person.

Many have derided the series for having a bias towards Steven Avery and his defense team. When I hear these complaints, it’s very clear that there’s a widespread misunderstanding of what a documentary is. Documentary filmmakers are storytellers. They capture and collect hundreds of hours of footage, carefully curate it, and then edit the relevant bits together to communicate a message, or story, to the viewer. There is no such thing as an “unbiased” documentary, because the very act of laying out a story or thought process for the viewer is inherently biased.

But what gives Making A Murderer its power is the sheer number of injustices that are presented, clear-as-day. There is simply no way that a rational person could watch the Brendan Dassey’s confessions, listen to his phone calls with his mother, know about the lack of evidence of his described crime, and believe that anything he said was true. Similarly, the convenient appearance of severely incriminating evidence eight days into the search of a single trailer, the obviously tampered-with DNA sample of Steven Avery at the lab, the evidence of multiple burn pits, the mischaracterization of the EDTA test, and the fact that all of these were essentially unquestioned is just a shame. If such conclusions are put in our heads by the biased storytelling of the documentary, than I challenge anybody to show how the they were mischaracterized. Nothing I have seen suggests so.

The series is occasionally flawed. It will sometimes suggest something nefarious on somebody’s behalf, such as Sergeant Colburn calling in Teresa Halbach’s plates and vehicles two days before they were officially found, or Mike Halbach’s strange dismissal of all evidence that points away from Steven Avery, or Teresa’s ex-boyfriend Ryan’s suspicious behavior, and then quickly back off. In these cases, it is planting seeds of suggestion in the audiences minds, making them feel like they’re figuring out “the truth” behind the story, without actually delving into its stealthily-made accusations. In these cases, it is essentially doing the same thing as the prosecution in the case: making allegations without fully examining the bigger picture.

In any case, Making A Murderer is an important series. It plainly portrays three trials that are all absolute farces, and suggests that the convictions that result are not anomalies. Our country currently utilizes a terribly broken legal system, one that often directly contradicts the principles on which it was founded. It’s unfortunate that it took a Netflix documentary to spread awareness and encourage a call to action, but it is clear that there is a desire for reform. We can only hope that these feelings don’t subside as soon as the Next Big Thing hits.