Just last week, one of Sony’s most high-profile exclusives, The Order: 1886, launched on the Playstation 4. However, before most people could get their hands on it or even read a review, a Youtube user leaked a video of the entire game, from start to finish. This in and of itself isn’t especially uncommon these days, but the video stirred up a lot of controversy by only clocking in at a little over 5 hours. For a $60 game, this seemed outrageous to many gamers, and a full-blown controversy emerged online.

Just last week, one of Sony’s most high-profile exclusives, The Order: 1886, launched on the Playstation 4. However, before most people could get their hands on it or even read a review, a Youtube user leaked a video of the entire game, from start to finish. This in and of itself isn’t especially uncommon these days, but the video stirred up a lot of controversy by only clocking in at a little over 5 hours. For a $60 game, this seemed outrageous to many gamers, and a full-blown controversy emerged online.

Critics (who, for the most part, DID NOT like the game) were quick to state that the 5 hour game length was only accurate if somebody rushed through the game as quickly as they could, and that most people could expect to get 7 or 8 hours out of it. This was still on the low-end of what game audiences are used to today. Some came to The Order’s defense, citing titles like Journey and Portal, fantastic games that could be beaten in under an hour. But those did not retail for $60.

Looking back on the last generation of consoles, The Order does not seem to be too offensively short. Some of the most revered AAA franchises, such as Halo, Gears of War, Metal Gear Solid, and Uncharted, all had similar lengths and nobody complained. So what happened since then to change the way that people perceive length? If you ask me, I would say that it mostly stems from Ubisoft.

More specifically, it all started with the Assassin’s Creed franchise. The first Assassin’s Creed was considered a major disappointment because there was so little to do, and most of it was repetitive. You simply ran off to do a small number of generic tasks (some as boring as sitting on a bench and looking at somebody), and you completed an assassination when you were finished. Then you got to do it all over again. Rinse, lather, repeat.

Ubisoft realized that they had a problem with this formula, and that if they wanted to make the Assassin’s Creed series a major AAA franchise, they needed to create more compelling content with which to fill out their world. This led to Assassin’s Creed II, a huge improvement over the original. This game had a much more interesting set of missions instead of the repetitive tasks, but in addition it had a map absolutely covered with optional things to do. Treasure maps, collectible feathers, shops to own, landmarks to buy, glyphs to track down and solve…the game was chock full of content.

A lot of that content was admittedly pretty lazy. It takes practically no effort on the development team’s part to drop a bunch of collectibles around the map and task the player with finding them. In fact, it’s a very similar way of increasing “replay value” as the collectibles used by a lot of early 3D platformers, except without the hassle of making the player track them down. Instead, most of these icons were revealed once an area was “synced” (or viewed from a high vantage point), meaning that players could spend hours simply running around a map, setting waypoints, and grabbing items.

To an outsider, it all sounds dreadfully boring. But given the mechanics of the Assassin’s Creed series, it worked wonders. The developers had realized from feedback of the first game that the real draw of the franchise was the freerunning mechanic, the assassin’s ability to leap over all sorts of obstacles and climb almost any surface. Since the traversal mechanics themselves were the draw of the game, tasking the player from getting from point-to-point gave him or her an excuse to simply enjoy the game’s strengths while making some progress.

Ubisoft realized that they had something, and they ultimately expanded this system into their Far Cry series with Far Cry 3. Like Assassin’s Creed II, Far Cry 3 proved to be far more successful than its predecessor and received rave reviews. While the game did not use mobility as its central draw, the incentivisation of collectibles and scattered waypoints led the player to exploring areas that they otherwise may not have bothered with. It also allowed for more random, unpredictable encounters with enemies and wild-life and made the world feel more alive.

Since then, Ubisoft has relied more and more on the “dotted map” strategy, incorporating it into nearly every game they’ve released. Meanwhile, other AAA developers have realized how effective it can be, so they have begun working the system into their games as well. At this point, it’s essentially a standard.

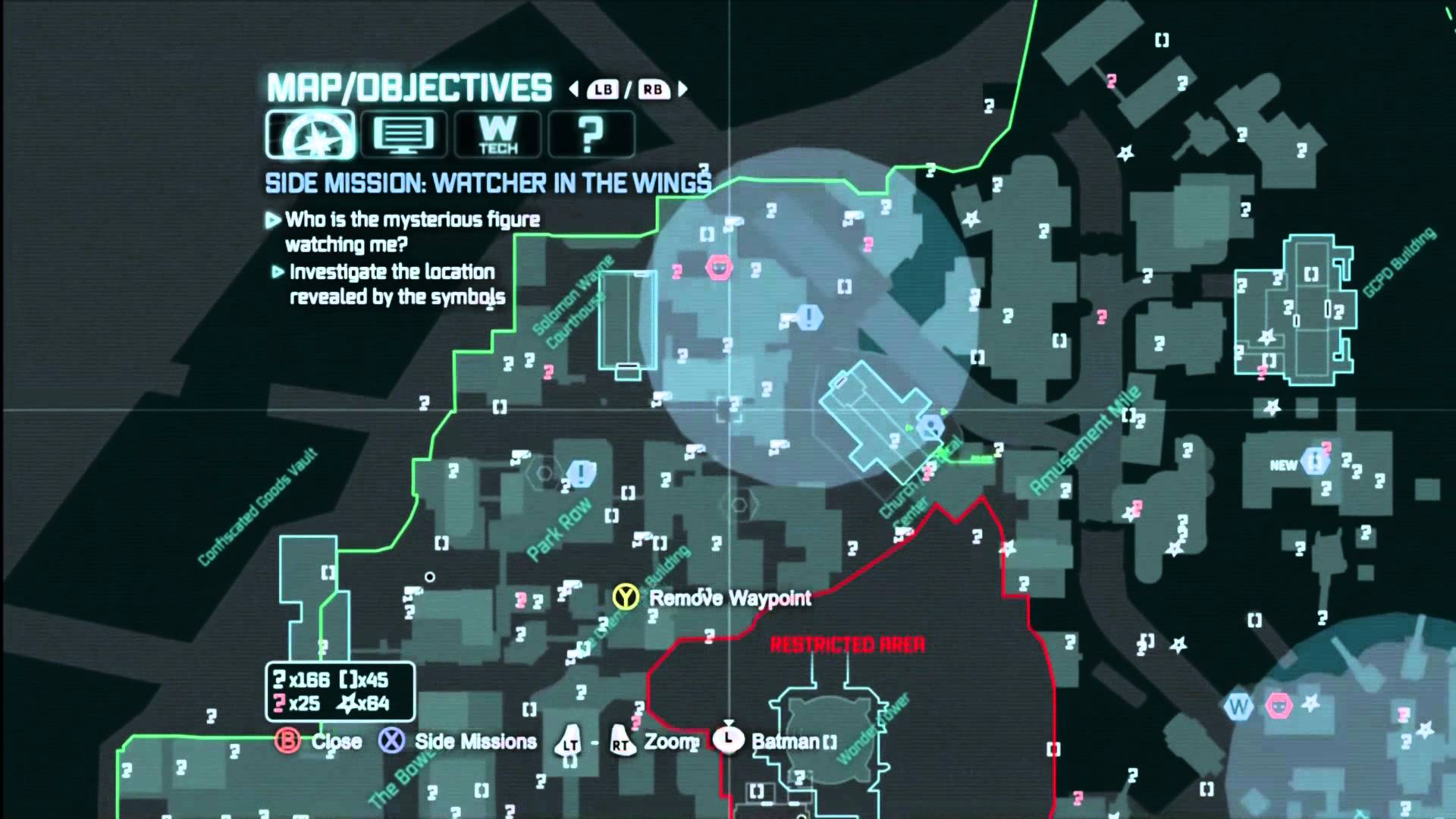

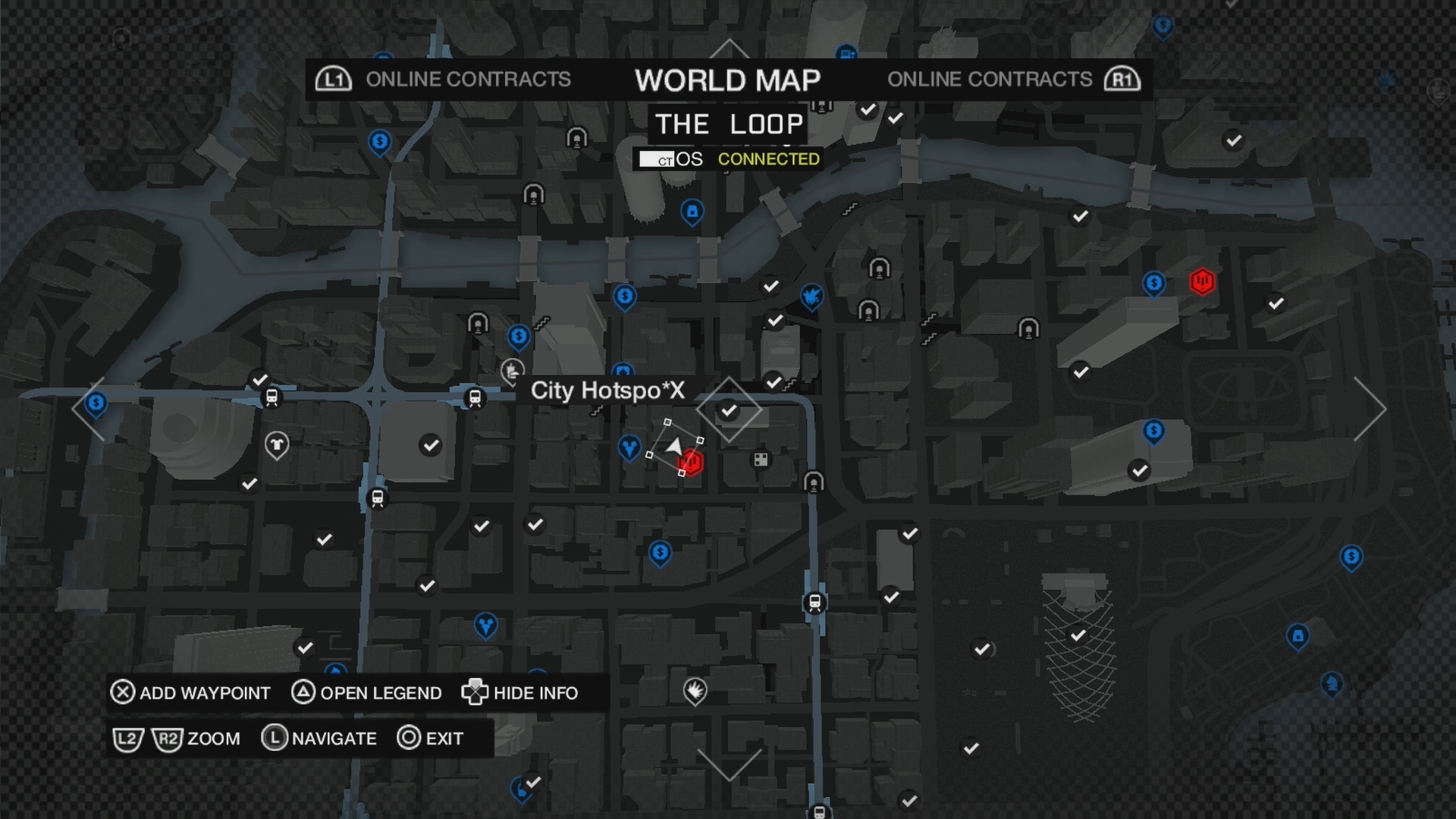

Don’t believe me? Let’s look at the maps of some of the most popular games of the last few years.

Middle-Earth: Shadows of Mordor

And Assassin’s Creed Unity, for good measure

The sprinkle-the-map-with-random-tasks-and-collectibles method isn’t always successful. Watch Dogs, for instance, is filled with utter junk content that has nothing to do with the game or its strengths, such as minigames involving bouncing on flowers or racing around collecting 3D clocks. And in Dragon Age: Inquisition, an otherwise phenomenal game, all sorts of uninteresting collectibles and simple tasks are scattered around every single location, drawing out the length to an absurd degree. The dotted map can lead to bloat, which can detract from the actual strengths of the game.

The effect of this strategy, for better or for worse, means that most AAA games are longer than they were 5-10 years ago. Due to the way that the game industry has split into $100 million dollar projects or tiny indie games (mirroring the film industry), this had led to an environment where $60 games come with the expectation of longevity and replay value, while $15 and under games come with the expectation of brevity and innovation.

Going back to The Order, length should not be our primary concern. Certain games simply function better when they’re not drawn out to interminable run-times. I wish it were as simple as saying that long or short games are “better” (that would have led to a much shorter article, for one thing), but perhaps it should fall to the developers to figure out the strengths of their individual titles before they decide on their length, or their system of replay value. And maybe we, as consumers, should stop avoiding games because of their perceived length rather than their supposed merits.

Thank you.