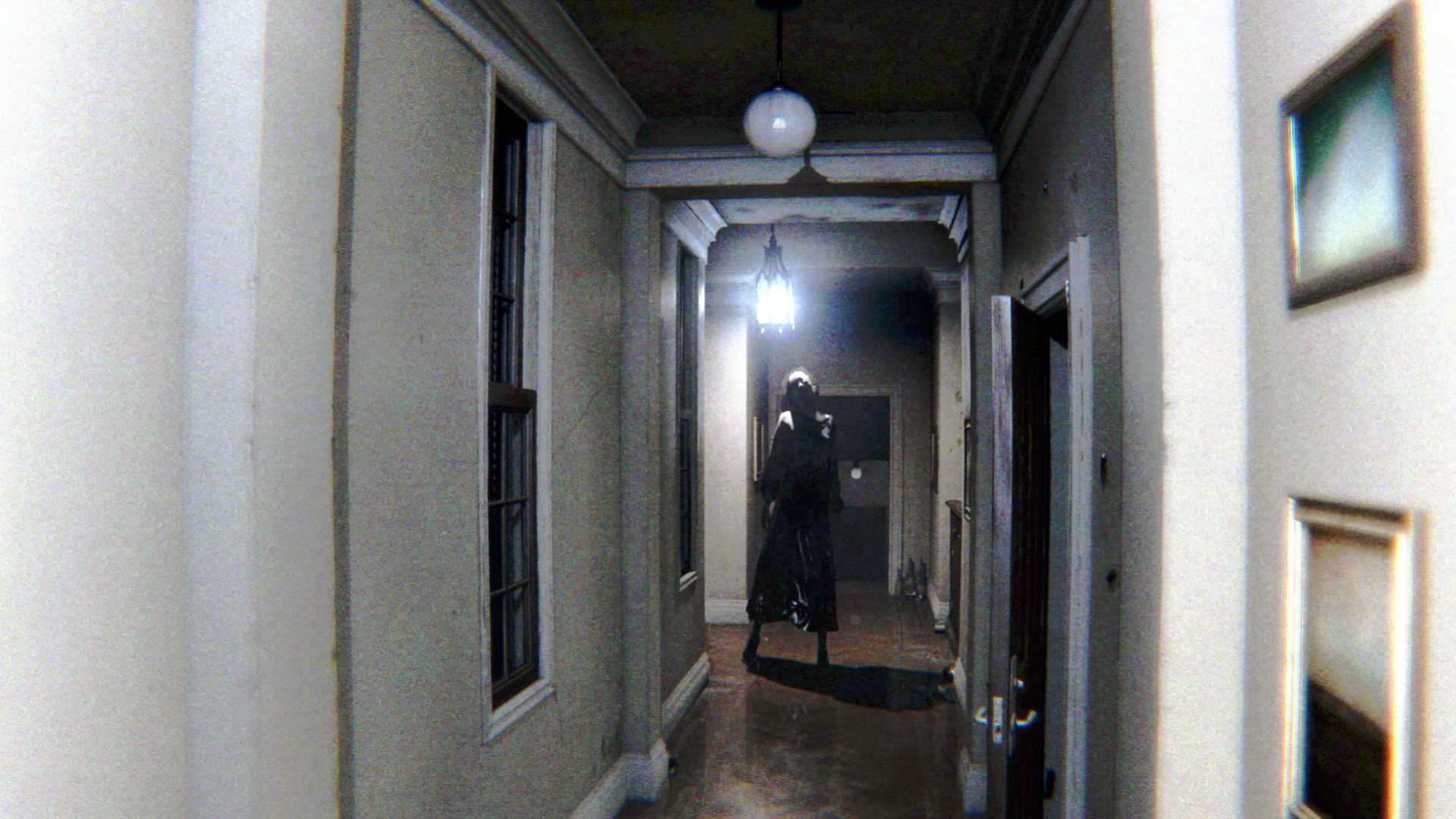

Last year, a free promotional game called P.T. hit the Playstation Store. It was a wildly inventive and terrifying experience, entirely set in a single repeating hallway. Unlike a lot of horror games, which rely on jump scares and enemy AI, P.T. felt intentionally and masterfully designed against your expectations. Complete game or not, it was a marvel of game design and, at least in my personal opinion, the most interesting video game released in 2014.

Last year, a free promotional game called P.T. hit the Playstation Store. It was a wildly inventive and terrifying experience, entirely set in a single repeating hallway. Unlike a lot of horror games, which rely on jump scares and enemy AI, P.T. felt intentionally and masterfully designed against your expectations. Complete game or not, it was a marvel of game design and, at least in my personal opinion, the most interesting video game released in 2014.

Enter today: Konami, the same company that published P.T., is trying to erase it from history. As I mentioned, P.T. was technically a promotional game, and the game it was promoting was Silent Hills, a reboot of the classic survival horror game series. That game (and P.T., by extension) was developed by legendary game designer Hideo Kojima and his team at Kojima Productions, in creative collaboration with Guillermo del Toro and starring Norman Reedus of The Walking Dead. Unfortunately, Konami has been on a roll of self-destructive decisions that ultimately led to the loss of Hideo Kojima from their company. While he’s staying on as a contractor to finish the nearly-complete (or, if you believe some rumors, the complete-but-standing-by-for-a-fall-release) Metal Gear Solid 5, his other projects are being killed. That includes Silent Hills.

This, of course, complicates things between Konami and the already-released P.T. Now that Silent Hills is officially dead (a fact that Konami initially avoided and was ultimately revealed by del Toro, who said that it “breaks [his] greasy heart”), P.T. has gone from a tantalizing glimpse into the future to an embarrassing token of Konami’s own failures. Alongside their official announcement that the project had been cancelled, Konami also announced that they were going to pull P.T. from the Playstation Store.

This not only affects future PS4 owners, but even those who already have the game. Unlike when a game is normally pulled from the Playstation Network storefront, P.T. has been completely erased from Sony’s servers, so it is now impossible to re-download. Players like me who still have P.T. on their console can play it (which is causing certain owners to try selling their P.T.-playable PS4’s on Ebay for $1000), but once it’s gone, it’s gone. If your console dies, or your hard drive fails, or even if you upgrade to a new hard drive (something entirely likely, given how inadequate the PS4’s 500 gb default is when most major game releases require an additional 40 gb of space), P.T. is gone forever. Within a few years, the game will be essentially extinct. And I can’t help but look at this and think “this is the future of entertainment.”

For years, we’ve been drawn in by the convenience and low cost of digital libraries and subscription services, and for good reason. Being able to subscribe to services like Netflix, Hulu Plus, and Amazon Prime, and getting access to thousands of movies and television series’ for only $8/month, is a great deal. These services give us so many entertainment options at all times that it has become near-impossible to truly justify boredom in this day an age. There is always something out there worth watching.

However, this interest in paying for access to enormous libraries of material has quickly diminished the interest in ownership of physical media. Blu-rays now appeal almost entirely to an enthusiast market, and DVDs, once the obvious and affordable medium for the casual movie-fan, are now encumbering, taking up precious space in our households and providing a video quality that is inferior to what is available on digital services. When so many options are available with a few hits of a button or clicks of a mouse, why spend money to watch something off of a plastic disc?

P.T. is the answer to that question: it’s all about the power of ownership. By letting physical media die and surrendering entirely to a digital entertainment landscape, we are giving the content providers complete control over what is and isn’t available to us. As often as companies have tried in the past to limit and control this marketplace, they’ve never been able to do so completely. No matter what is in and out of the Disney Vault, you’ve always been able to seek out a Disney movie from a previous owner looking to sell. No matter how much the RIAA wants to claim that CD ownership only offers you a license to personally listen to their music, you can always buy and sell used CDs at music stores. George Lucas can talk all he wants about wanting to smash every single copy of the Star Wars Holiday Special with a hammer, but he’d still have to buy a hell of a lot of plane tickets to do so.

Physical media, as space-consuming and sometimes costly as it is, empowers the consumer rather than the content creators. It is the only way to be sure that you really own the things that you think you own. As we get further and further from true ownership of content, we begin to forge a future where entertainment creators and content providers can not only choose what they want to provide to consumers, but also re-author their own histories. Why continue offering, say, an embarrassing high-profile flop, if you can simply erase it from servers and pretend it never happened? Or what about when a studio acquires a new property and wants to erase all previous efforts with it? In an all-digital access-based landscape, they have the power to do so. If all that exists of a past work is the memory of the people who experienced it, then does it effectively die with them?

Look back to the silent era of film, for instance, before film preservation and home video copies existed. While those of us interested in film love to pore over these early efforts and watch the medium grow, according to Martin Scorsese’s film foundation, over 90% of films created before 1920 are lost. They do not exist in any current state, and are completely inaccessible. We’ve made such great strides in film preservation since then, but these strides were often funded by studios and motivated by the option to create new transfers to sell to consumers. Without ownership as a financial motivator, and with streaming services already leveraging hundreds of other titles that might appeal to the same target audience, then why continue preserving works at all? Isn’t it cheaper and more appealing to preserve the more convenient pieces and eschew everything else?

The P.T. situation suggests that it is easier, and that companies will absolutely stoop to that level if they can. Please, do not read this as a screed against content access providers: I personally subscribe to Netflix and Amazon Prime, and think that they are fantastic services. Instead, take this as a rallying cry for the co-existence of physical media. The movie studios and content providers already have control over the future of art and entertainment. Don’t let them control the past as well.