You read the headline right: I am just now getting around to reviewing The Witcher 3: The Wild Hunt. It’s not that the game went under my radar. I actually went against my “never pre-order” rule to support GOG.com, which is completely DRM-free and handed out discounts to anybody who owned previous Witcher titles. So I’ve had The Witcher 3 since its release on May 19th, and yet I just finished it. My final gametime clocked in at exactly 100 hours, and I still had a couple of treasure hunts left unfinished.

Given the above, I don’t have to elaborate on how much time you can sink into The Witcher 3. But just because a game is lengthy doesn’t mean that the time you spend within it is worthwhile. I have 200 hours logged in Destiny, yet the vast majority of that time was spent re-playing the same old missions ad-infinitum. Similarly, I spent almost 80 hours in Metal Gear Solid V, but the majority of that was in Side Missions, which re-use environments that are already present in the main game. Even in other huge-scale RPGs, like Dragon Age: Inquisition and Bethesda’s RPGs (Elder Scrolls, Fallout), a handful of quests are interesting and memorable and the majority are fetch quests or “go here and kill this monster” missions.

The most remarkable thing about The Witcher 3 is how completely engaging its side content is, to the point where it often usurps the actual central narrative. When you take on a Witcher Contract, which is the closest thing the game has to a “kill the monster” quest, there’s always a story behind it. Polish Developer CD Projekt RED recorded a ton of dialogue for each quest, so player-character Geralt can always learn a lot from whatever character put out the monster contract. Sometimes there’s a missing family member involved, sometimes a ravaged town, and sometimes the whole scenario is a trap or a scam. This lends an unpredictability and a spark of life to a quest structure that is so by-the-numbers elsewhere.

The actual process of hunting a monster is different in The Witcher, as well. Because Geralt is a witcher (a being mutated and trained to be an expert at monster tracking and an unmatched combatant), you don’t simply run off into a monster lair with your sword held high. You have to be smart about it. Geralt can interrogate locals for extra information on the beast, comb over the scene of an attack for extra clues, and prepare himself with potions and blade oils to best counter whatever beast he expects to face. Then he can track the monster by footprint or smell, until finally killing the beast and taking a trophy.

Yet despite being so fleshed out and so numerous (skimming my “complete” contracts, there appear to be 28), the Witcher Contracts are only a small part of the game. In addition to “Treasure Hunts,” which are the closest thing The Witcher has to fetch quests (and even those have specially-written letters that lead you on the right path), the game contains a mindbogglingly huge number of “Secondary Quests.” And despite the “secondary” nature of their title, there is nothing half-assed about these.

The majority of side-quests (of which there are MANY; I count 63 on IGN’s Side Quests page, not including Contracts, Scavenger/Treasure Hunts, or DLC) are just as well-written and and intriguing as the main quests, and sometimes even more consequential. One particular line of side quests involves the assassination of a king, and it has more impact on the world at large than almost anything Geralt does in the “main” storyline. The secondary quests also significantly flesh out Geralt’s friends and lovers. Every one has his or her own set of quests which illuminate the character’s nature as well as his or her relationship with Geralt. Some of the greatest, most memorable moments in the game come from these quests.

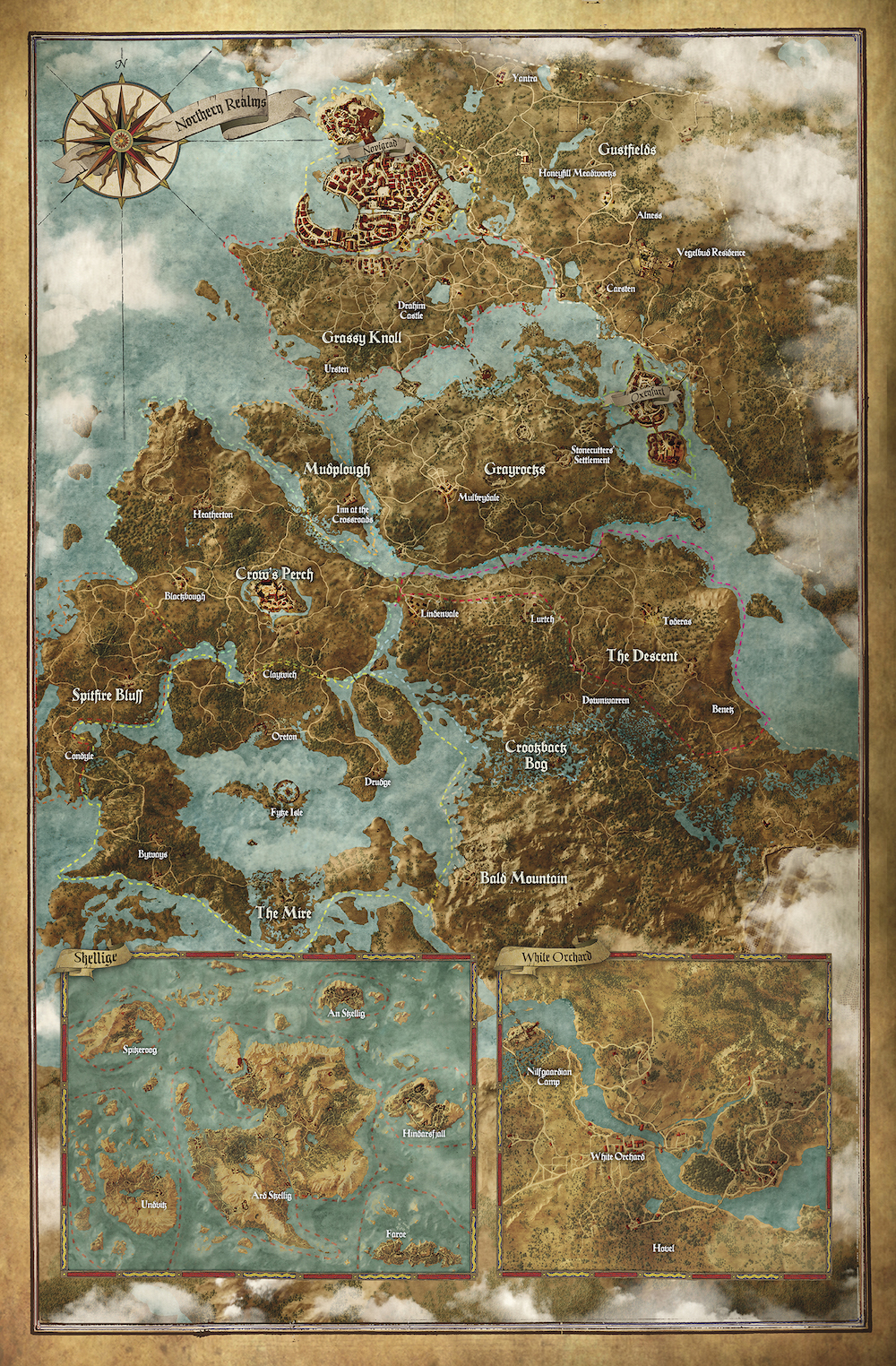

All of these optional missions and extra storytelling would still grow dull over 100 hours of gameplay if the world itself weren’t so alive. First of all, let’s just marvel for a second at how utterly enormous the game’s map is:

A couple notes on that: First of all, the “Skellige section below is shrunken for the image, and is actually roughly the same size as the “Northern Realms” portion of the map in-game. There’s also a whole extra section not included on this map which is roughly the size of the “White Orchard” inlay. The Witcher 3’s world is positively gargantuan.

Even more impressive, the CD Projekt RED team designed every single location by hand. No procedurally-generated worlds, no copy-and-pasting of landforms: it’s all unique and distinctive. The designers have said that they did not even bother creating a region until content had been created that called for it, so no space feels like filler. It all has a reason for existing in the world, lending every aspect of the game a sense of identity.

In fact, identity is another huge part of the reason why The Witcher 3 is so phenomenal. Unlike many Western RPGs, which ask the player to create their own avatar and decide on their race and background, The Witcher 3 is always going to be about Geralt. This means that character interactions, which are generic by necessity in so many other games, are heavily influenced by your social status and reputation as a witcher. Many lowborn folk will call you a freak, or tell you to scram, or if they need your expertise, begrudgingly approach you for help. Being one of the last remaining witchers in the game’s world gives you a different perspective on the game’s world. You’re more knowledgeable and worldly than nearly any other character in the game, yet a complete outsider as well. It makes the already dangerous worlds of Skellige and the Northern Realms even more alien and uninviting.

Fortunately, Geralt has learned how to cope quite well. He has a dry, sardonic wit about him which offsets his “scarred badass with a sword” visage and makes him surprisingly endearing. We also get to experience a number of moments which allow Geralt to come out of his shell and simply enjoy himself. Some of the game’s highlights involve getting drunk with friends, or entering into a snowball fight with your surrogate daughter Ciri. The Witcher 3 toys with a number of disparate tones, but juggles them appropriately throughout.

It’s a testament to the game’s myriad of strengths that I’ve now written more than 1000 words and barely touched on the main quest. The good news is, if you’re pressed for time and only want to accomplish the bare minimum, The Witcher 3 is still a superb game. The majority of the central story has you searching for the aforementioned character Ciri. However, during this portion of the game, Ciri functions more as a living MacGuffin device than an actual center to the narrative. Geralt follows up on clues as to her whereabouts, and gets embroiled in numerous barely-related conflicts along the way.

One could argue that spending so much of the main quest’s runtime on only vaguely related storylines is a missed opportunity, but I actually liked the approach. It meant that even players who avoided secondary quests altogether got a wide variety of stories, and that CD Projekt RED was still able to give the various regions of the world some characterization. Characters like the Bloody Baron and Dijkstra have very little to do with the search for Ciri, but their individual stories are interesting in their own right and open up even further if the player decides to continue them in the secondary quests. And the game wraps up very well, allowing plenty of time post-reunion to establish Geralt and Ciri’s relationship and offering up a multitude of different endings.

If there’s one drawback to The Witcher 3, it’s that the actual act of controlling Geralt isn’t especially groundbreaking. Like The Witcher 2, you have direct control over his movement and combat. Combat itself is made up of quick attacks, slow attacks, and Geralt’s five “signs,” which are basically spells. It’s all plenty functional, and there is some degree of customization in the “Character” section of the menu, but it’s ultimately secondary to the game’s narrative. The Witcher 3 views its game mechanics as a way to experience its story, not the other way around, so while it functions beautifully as an open-world game, it is in no way a “sandbox” game. Most quests only have one way to accomplish them, making it seem limited in the face of something like Metal Gear Solid V, or some of Bethesda’s RPG titles.

But any lack in core gameplay variety is overshadowed by the scope of the game and the specificity apparent in every element of its design. The Witcher 3: The Wild Hunt is a towering achievement in game design, one which shames its competition. In an industry which has grown complacent with artificially extending game length through repetitive and computer-generated filler, the Witcher 3 is a beam of light in the darkness, proof that hard work and a dedicated team can make all the difference.