(Note before reading: This article contains examples from Bioshock, Bioshock Infinite, and The Stanley Parable that may be considered spoilers. In the case of Bioshock, the example is a pivotal moment in the game and best left unspoiled if you are interested in playing it in the future. The examples from Bioshock Infinite and The Stanley Parable are less pivotal, but also reveal the main philosophies behind those games. The Bioshock Infinite segment mentions a couple rather unique locations from the end of the game, as well. If you want to remain completely unspoiled, do not read ahead.)

(Note before reading: This article contains examples from Bioshock, Bioshock Infinite, and The Stanley Parable that may be considered spoilers. In the case of Bioshock, the example is a pivotal moment in the game and best left unspoiled if you are interested in playing it in the future. The examples from Bioshock Infinite and The Stanley Parable are less pivotal, but also reveal the main philosophies behind those games. The Bioshock Infinite segment mentions a couple rather unique locations from the end of the game, as well. If you want to remain completely unspoiled, do not read ahead.)

When does a form of storytelling or expression become its own artistic medium? Was film a medium as soon as Edison began to showcase the May Irwin kiss (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IUyTcpvTPu0), or was that just an early example of a technical achievement? When our ancient ancestors began to scribble the likenesses of men and animals on the sides of cave walls, had they created two dimensional art? Or were they just experimenting?

I’ve talked before about how the earliest examples of most artistic mediums are imitations of something else the creator is already familiar with. The earliest paintings and sculptures are the likenesses of people and things that existed in nature, or they are representations of symbols important to the creator’s spiritual beliefs. With more modern mediums, the early creators used other similar mediums as guideposts. This is why, when film stopped being a curiosity and instead became a method of storytelling, it largely imitated theatre until filmmakers realized how powerful close-ups and montage could be.

For me, a medium really comes into its own once its strengths and limitations are defined enough for artists to comment on them within the medium itself. This is called medium reflexivity, and examples can be found in all mature mediums. The works of M.C. Escher are often a strong example of this: he drew impossible stairways and connections in “Relativity” to show how limiting perspective to two dimensions alters reality, and created “Hand with Globe” to make the spectator of a piece (the glass globe) an actual participant in his own work of art.

A fun example in animation is Chuck Jones’ Looney Tunes classic, “Duck Amuck” (http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/ccManager/clips/duck-amuck). The artifice of animation is pointed out in several ways here: the limitations of the environment to what’s onscreen, the disconnect between the hand-drawn animation and the audio, and the fact that the whole short is at the whim of an off-screen creator.

In the case of film, examples of reflexivity go all the way back to the silent era. In Josef von Sternberg’s The Last Command, a Russian general is stripped of his power during the Russian Revolution and ends up in Hollywood as an extra, forced to work on a film adaptation of the very events that deposed him. Here, we get to see the same event in multiple forms: both as a “real” revolution within the film’s narrative, and as a “film” version, complete with fans for wind and fake snow. However, as a viewer, you are aware that both versions of these events are actually fabricated. If anything, the end of the film illuminates the artifice of cinema in general.

Finally, I come to a medium that’s new enough that we still aren’t sure how to refer to it: Video games. Gaming. Electronic entertainment. Interactive arts. For decades, the evolution of gaming as a medium was more technical and functional than artistic. We started with 2D pixel-drawn games, limited to one screen. Since then, we’ve seen games introduce scrolling (the ability to move far enough left and right that the screen scrolls to reveal more of the environment), simulated 3D visuals (such as Super Mario Kart and F-Zero’s “Mode 7” visuals on the SNES, or Doom’s simulated 3D environments), actual polygon-based 3D visuals, then 3D movement and exploration. Over the last couple decades, 3D worlds and the engines that drive them have become complex enough that, with a big enough team of clever developers, just about anything is possible.

Now that developers are less concerned with breaking technical ground, they’re starting to really think about what differentiates gaming from other mediums, and where its limitations lie. The most evident factor for both is “choice.” The whole point of an interactive experience is that the audience is an active participant: They can go where they want and do what they want. But are these choices meaningful, or do the limitations of the medium render them meaningless?

One game that seeks to address this matter is Irrational Games’ 2007 release, Bioshock. In Bioshock, you play an unseen protagonist named Jack whose plane crashes in the sea near a lighthouse. After exploring the lighthouse, you find yourself submersed deep below the sea in an underwater city called Rapture. Formerly an Objectivist utopia, the hubris of Rapture’s most brilliant inventors and creative minds ultimately brought the city to ruin. You find yourself wandering through the remains of the city, helping a man calling himself “Atlas” rescue his family from the powerful business magnate Andrew Ryan, who is apparently holding them within a bathysphere.

After spending 2/3 of the game helping Atlas track Ryan down, you come face to face with the man, only to discover that things are not quite what they seem. “Atlas” is really a former gangster and direct business competitor of Ryan’s named Frank Fontaine. Throughout the entire narrative he has been mind controlling you, forcing you to do whatever he says with the seemingly harmless trigger phrase “would you kindly.” You then are forced to kill Ryan, regardless of whether you would like to do so, because Fontaine gives you the order.

But wait, haven’t you been the one controlling Jack throughout the duration of the game? How could you have been controlled and forced to do these actions, given your own agency in the story? Up to that point, your actions had been framed by empathy for Atlas (whose “family” was never actually being held by Ryan in the first place). But given the restrictions and linearity of the game, you never really had any choice in how things would proceed.

This is true of almost all narrative-driven games. Even if you have a few different paths to take, or options in how to take out enemies or proceed, you’re ultimately on-rails. There is a goal, and you will get there in a similar fashion to other players. We rarely question it, but we might as well be mind-controlled given the lack of true agency in the progression of the story. It’s not like we can simply listen to Atlas’ request for help, say “no thanks” and leave Rapture: the game would never end. By taking the limitations inherent in all narrative-driven games and shining a spotlight on the protagonist’s lack of agency, Irrational Games is asking us to reflect on and question the medium without being overtly didactic.

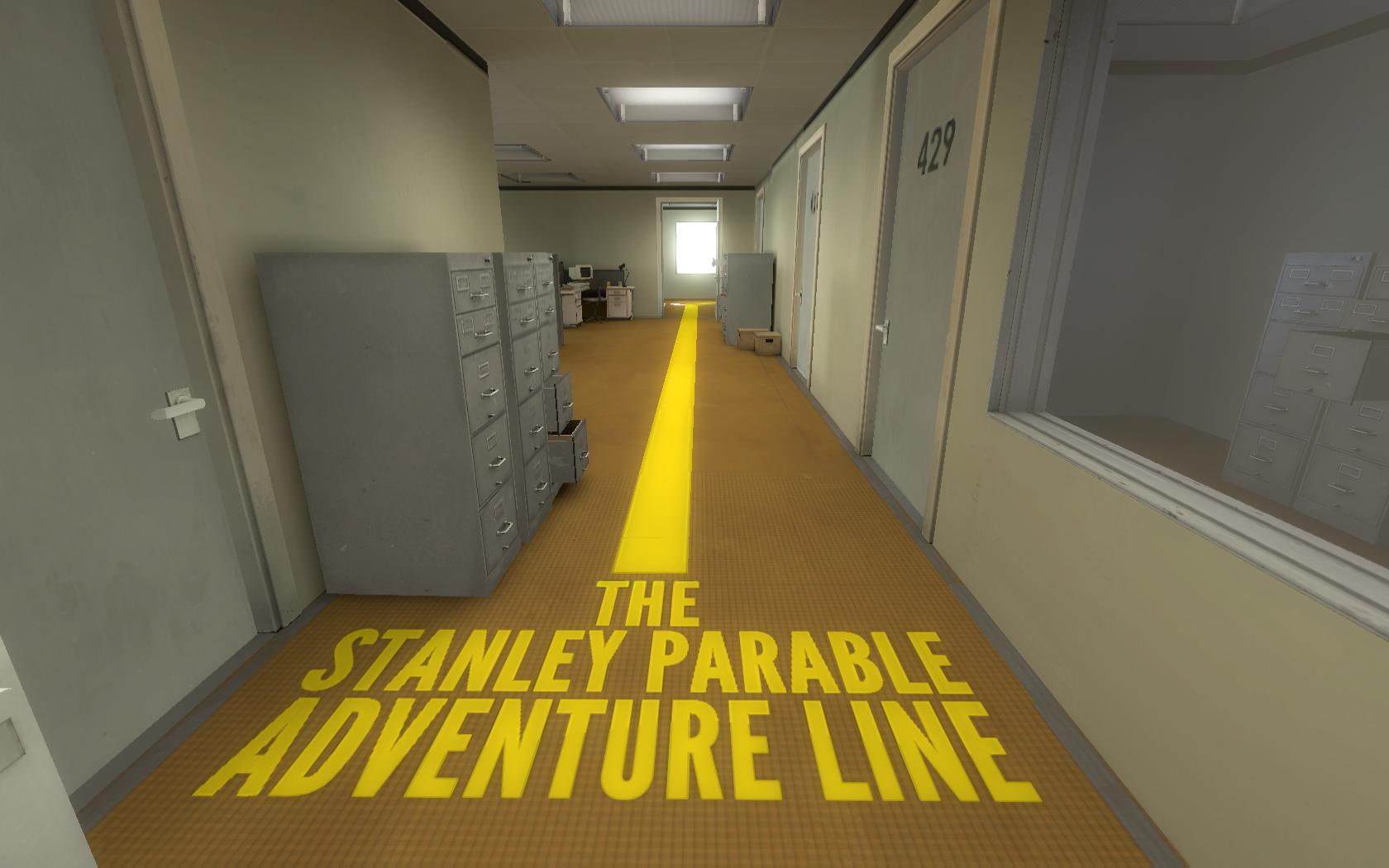

But what about games with choices, like The Walking Dead or Heavy Rain? Where there are multiple paths, and endings? Galactic Cafe’s “The Stanley Parable” tackles the concept of multiple endings and more.

The central “story” of The Stanley Parable is rather simple. You play as Stanley, a man who works for a company and sits around pressing buttons for work most of the day. He loves it. One day, all of his coworkers seemingly disappear. You control Stanley as you wander through the office, while a narrative voiceover guides you through the experience. It will tell you that Stanley “walked through the door on the left,” or “went up the stairs to his boss’ office.” Following these directions, you eventually realize that your entire office is subject to a malicious mind-control device located below the office. Stanley ultimately shuts down this device, freeing himself from the control of others and allowing himself to walk freely out of the office. The whole game takes roughly 10 minutes to complete.

The irony in following the explicit directions of an all-knowing narrator in order to free yourself from mind-control is fully intentional. The game expects to you deviate from its path, either on your first playthrough or on repeat games. These deviations serve to illuminate (often hilariously) the limitations in any sort of “choice” in games.

For instance, what if you turn the Mind Control device power on instead of off? Doesn’t that kind of screw up the intended message of the game, leading to a dissatisfying conclusion? Well, yeah, and the narrator will punish you (with a clever subversion of a popular gaming trope). What if you die? Isn’t that your choice? Sure, but it’s not very satisfying either. What about a glitch? Does “breaking” the game prove your agency, or does it just defeat the purpose of playing the game in the first place? How do you know a glitch isn’t intentional? What if you find unfinished portions of the game? Does that increase your power over the narrative, or does it just further shatter the illusion of a world of infinite choice? Does adding a third door to a room add more player agency, or is it just another illusion of choice that ultimately railroads you to the same limited game world?

The game’s argument is that, no matter how complex a game world is or how many things you can try, there are always limitations. You’re still just a lab rat, either going through the motions pre-determined by a creator or intentionally going against the wishes of the designer and breaking the game in ways that are less satisfying than what was intended. The Stanley Parable posits that the only way to TRULY win, to shut down the developer’s “mind control” over the player, is to quit playing and do something in the real world, where the possibilities actually are endless.

If this is so, and everybody’s experiences are so limited, then why make and play games at all? Why not just watch a movie? It’s just as dependent on visuals, and you’re technically not losing any real agency, right? Irrational Games’ follow-up to Bioshock, Bioshock Infinite, tackles this quandary, albeit in a bit more subtle of a way than its predecessor.

First of all, there are the Lutece twins. I won’t spoil their actual part in the story here (Bioshock Infinite is less than a year old, and much more driven by plot and character than, say, The Stanley Parable), but they appear throughout the game, essentially keeping tabs on what elements of the narrative can be changed and what cannot. When you flip a coin, is the result ever different? Is it possible for the player NOT to win a lottery near the beginning? When given the choice of a couple of brooches, can the player pick a different one? Does any of this have any impact whatsoever over the course of the game? It is true that, within the narrative, they are exploring the limitations of something a bit different than a simple video game, but the reflection on the medium of gaming is certainly there.

This becomes even more clear towards the end of the game, where a character leads the protagonist through a sea filled with lighthouses, just like the one at the start of the game, as well as the original Bioshock. Each lighthouse represents a different possible universe, with a different man creating a different extremist society. The character explains that, within these universes, there are constants and variables. Certain factors, like the man and his city, are unchangeable. However, several other elements can vary wildly.

In addition to explaining the nature of the Bioshock series, this can also be extrapolated as commentary on the very nature of gaming. For instance, every player who completes Bioshock Infinite will experience the same general story, most of the same dialogue, and the same ending. However, the minutiae of their experience could vary quite a lot. One player may explore certain areas of the city more than another. Certain dialogue can be missed or paid attention. The various battles throughout the game can be approached in several ways, and the places in which the player dies will never be consistent from playthrough-to-playthrough. Despite the shared experiences most players have, every player technically has a unique experience as well.

This is further cemented when the player walks through one lighthouse door and finds himself on a pier, staring out onto countless other piers, each with another version of himself and his companion. Each one of these could be rationalized as another player of Bioshock Infinite, each with his own unique experience with the game, crossing paths at one particular moment that they all share.

None of these examples is the end statement on choice and agency in gaming. As the medium further matures, I’m sure we’ll see plenty of other ruminations within and without of actual games. Many, many game enthusiasts are having conversations and arguments over whether or not the choices in games like The Walking Dead and Mass Effect matter, given the endings are relatively limited. Is only the end result relevant? Or do our various choices throughout a journey shape our experiences in a way that is unique from all other mediums? Some may argue the former, but the longevity of the gaming medium may ultimately prove otherwise.

(All of the above games are available on PC. Bioshock and Bioshock Infinite are also available on the Xbox 360 and Playstation 3)