Part 1:

Part 2:

Part 3:

Part 1:

Part 2:

Part 3:

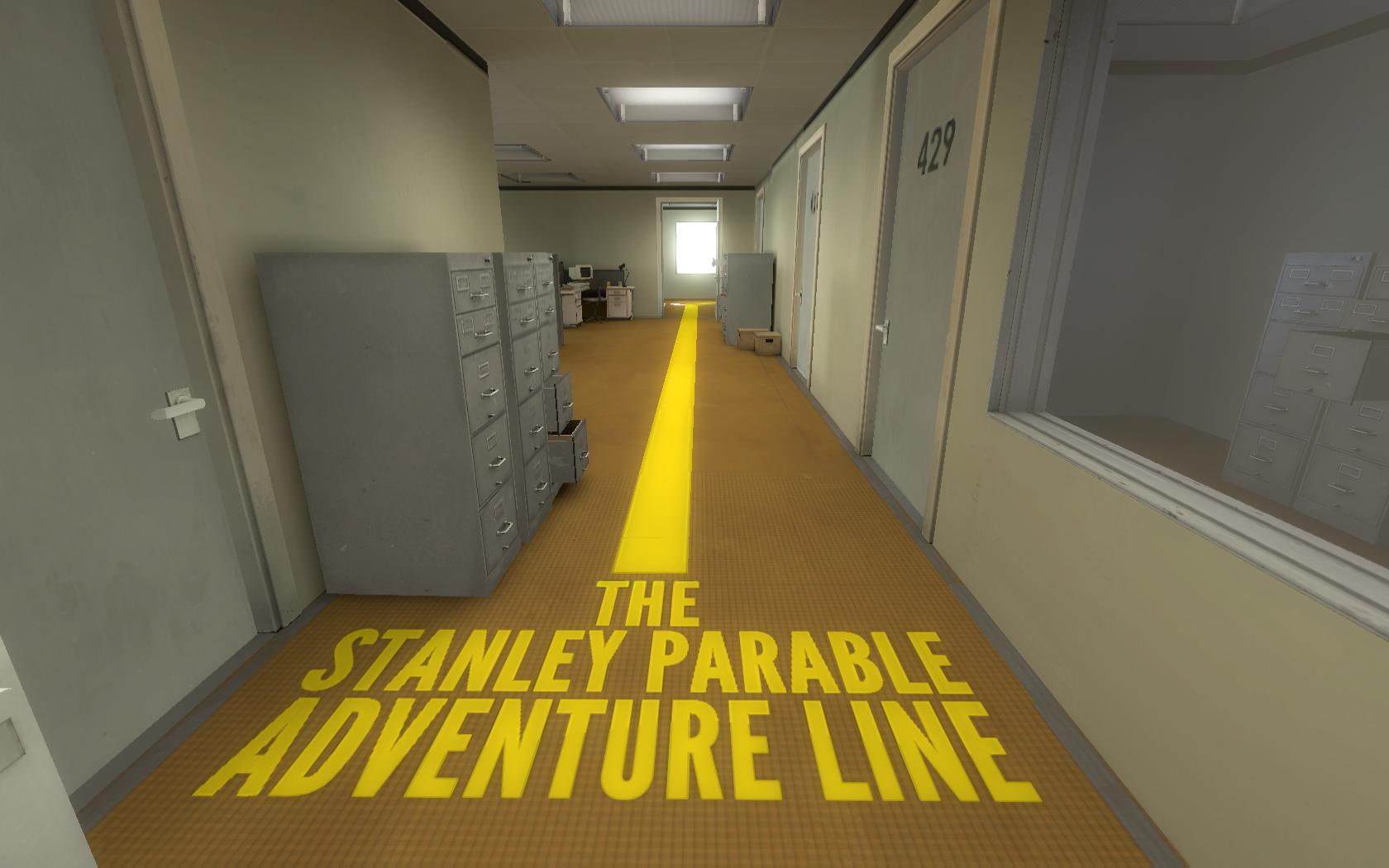

(Note before reading: This article contains examples from Bioshock, Bioshock Infinite, and The Stanley Parable that may be considered spoilers. In the case of Bioshock, the example is a pivotal moment in the game and best left unspoiled if you are interested in playing it in the future. The examples from Bioshock Infinite and The Stanley Parable are less pivotal, but also reveal the main philosophies behind those games. The Bioshock Infinite segment mentions a couple rather unique locations from the end of the game, as well. If you want to remain completely unspoiled, do not read ahead.)

(Note before reading: This article contains examples from Bioshock, Bioshock Infinite, and The Stanley Parable that may be considered spoilers. In the case of Bioshock, the example is a pivotal moment in the game and best left unspoiled if you are interested in playing it in the future. The examples from Bioshock Infinite and The Stanley Parable are less pivotal, but also reveal the main philosophies behind those games. The Bioshock Infinite segment mentions a couple rather unique locations from the end of the game, as well. If you want to remain completely unspoiled, do not read ahead.)

When does a form of storytelling or expression become its own artistic medium? Was film a medium as soon as Edison began to showcase the May Irwin kiss (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IUyTcpvTPu0), or was that just an early example of a technical achievement? When our ancient ancestors began to scribble the likenesses of men and animals on the sides of cave walls, had they created two dimensional art? Or were they just experimenting?

This write-up was written under the assumption that the reader has watched all of Breaking Bad. Please be aware that there are spoilers from the entire series within, and proceed with caution.

This write-up was written under the assumption that the reader has watched all of Breaking Bad. Please be aware that there are spoilers from the entire series within, and proceed with caution.

There’s a great scene towards the end of Paul Thomas Anderson’s film The Master in which the film’s title comes to light. After Joaquin Phoenix’s Freddie Quell returns to Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Lancaster Dodd following a long absence, Dodd explains that we’re all slaves to our “masters,” the drives and motivations that inform every decision that we make. The speech explains a lot about about Freddie, who has spent his life substituting his love for a woman with extreme alcohol abuse, followed by religion, and eventually a renewed appetite for women. Whenever he felt the need to give up one “master,” a hole was left in his being that he needed to fill with a new one.

[Regarding spoilers: I do talk about a few plot points below, but the majority of them are in broad strokes. I mention some of the mysterious elements in the first season of Lost, and the general plot descriptions of a few episodes of Under the Dome. There are also a couple of relatively specific plot points from the show Flashforward. None of these are particularly explicit, and I certainly would not expect them to ruin the shows in question for anybody. However, if you are concerned about knowing anything AT ALL about Lost or Under the Dome (the show, not the book), you may want to avoid reading this article. I would consider this article spoiler safe, though]

[Regarding spoilers: I do talk about a few plot points below, but the majority of them are in broad strokes. I mention some of the mysterious elements in the first season of Lost, and the general plot descriptions of a few episodes of Under the Dome. There are also a couple of relatively specific plot points from the show Flashforward. None of these are particularly explicit, and I certainly would not expect them to ruin the shows in question for anybody. However, if you are concerned about knowing anything AT ALL about Lost or Under the Dome (the show, not the book), you may want to avoid reading this article. I would consider this article spoiler safe, though]

The most traditional, popular form for a TV drama is the procedural. Usually, a procedural follows a professional team of some sort (cops, or investigators, or doctors, or lawyers) as they take on a new case every week. It’s a simple, solid formula that is still abundant in network programming because it’s effective. Since each episode is a new story, new viewers can easily jump in and start watching at any moment, and they don’t have to worry about missing an episode from time to time. However, because procedurals follow the same team week-to-week, the viewer starts to feel familiar with the characters on the show. A good procedural is the epitome of “hang-out” television: there’s little commitment on the part of the viewer, but watching the show starts to feel like dropping in on old friends.